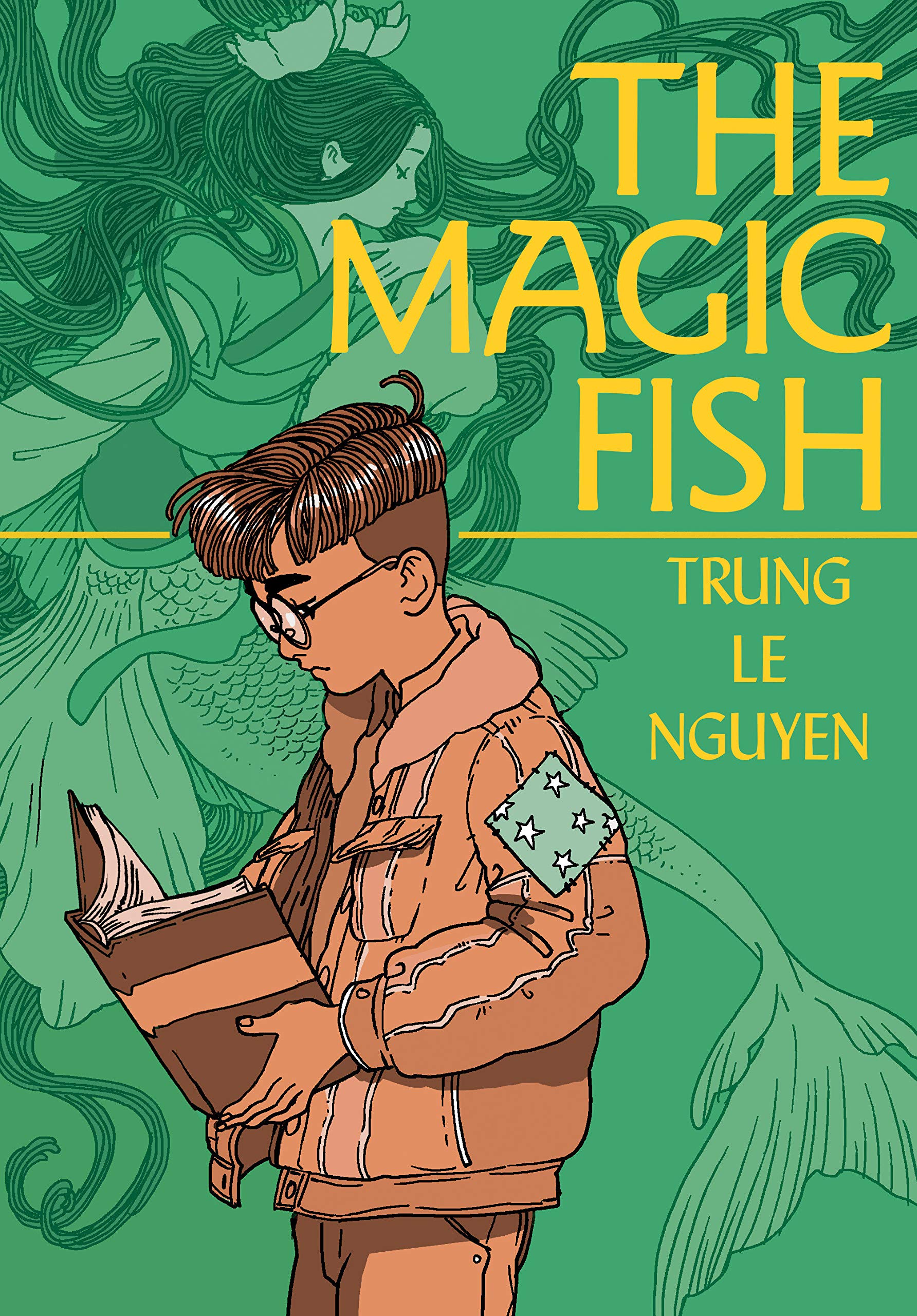

The Magic Fish (and all my feelings)

The Magic Fish by Trung Le Nguyen (also known as Trungles) is a graphic novel about a young boy finding words between worlds, life between cultures, and the power of stories. Tiến, the main character, is trying to find the words to come out as gay to his parents, Vietnamese immigrants. His mother Hiến is far away from her own mother, having come to a new country. The graphic novel intertwines the fairy tales they read together in English with the tales of their own lives as they find the words to come together.

I had been meaning to read this book forever, but it was only recently that I finally picked it from my library. I’d constantly heard great things about it from both random people on the internet and people I trust. All those things were well-merited! I came to this book looking for a reflection of myself, words of guidance, and something like a feeling of not being alone and I think I found all of those things.

I’ve always been interested in fairy tales and in the ways they are told, how they evolve, and how in them we can see echoes of our own lives. The fairy tales in this book wove Tiến’s life and the fairy tales particularly well. At first, I wasn’t sure exactly how the story was going to be framed (all I knew about the book was fairy tales, finding words to come out, nothing particularly revealing) but once I understood that the parents and Tiến were reading together to learn English, it made a lot of sense. It made me wonder if the times my dad read stories to me when I was child were also a way for him to practice his English.

I went into the book expecting the darker (read, less Disneyfied) aspects of the stories, but I was unfamiliar with the specific sources that Nguyen based the stories in the book on (in the notes afterward, they name Allerleirauh and Tấm Cám, as well as the Little Mermaid and the ballet Ondine). I appreciated that The Magic Fish did not shy from the horrors that can be found in fairy tales but also did not linger on despair. There were some heavy and emotional moments in the story, yes, but there was hope.

I think the thing that hit me the most in this book was just the way it illustrated an escape from repeating the pains of the past. There’s an exchange in the story, where Tiến’s mother listens to a story from her sister:

"Is that how it goes? I can hardly remember."

"Probably. They're only stories. They'll change when they need to."

and in the story of Tiến’s coming out and his relationship with his mother, we see that in action in a very poignant way. I definitely cried.

And look, I was prepared to cry, because the story in this book was a reflection of my real life (sort of). I came out to my Filipino parents last December and it was terrifying because we just never talked about these sorts of things. And I knew the Tagalog word for gay (but not for bisexual or any other words for queer), but I don’t know if I could say whether I’d ever heard it in a particularly affirming way in the times my parents would talk about people they knew or friends of relatives. (And being me, I did come out in a letter first, because speaking words out loud has never been one of my strengths.) In their own way, I think my parents are coming to understand that this is our story now. My life has maybe not progressed according to the story they were telling themselves, but in our weekly phone calls (where we talk about food and gardening and East Asian dramas, because that is our version of fairy tales, I guess) we are weaving a new tale. (and it might not be perfect, but it’s ours and maybe we’re growing, if a little more slowly than the basil in the Aerogarden they got for Christmas)

Anyway, this was a ramble, but I had feelings. Read this book, and you will, too.